Deep tech often gets used as a compliment, a pitch deck garnish, and occasionally as camouflage. It’s frequently misunderstood.

In its simplest form, deep tech describes companies building technology rooted in breakthrough science or meaningful innovation in engineering — the kind that takes real R&D, real time, and usually real capital before it’s ready for scale. This framing is consistent across both practitioner and institutional definitions of the category. [1][2][5]

What makes deep tech deep is the shape of the risk. Often, the primary risk is technical (can we make it work, reliably, at cost?) long before it becomes purely market (can we sell it?). That’s why deep tech timelines and financing look different from “regular” software. [1][2]

This guide does three things:

- Defines what deep tech is in plain English

- Draws a clear line around what it isn’t

- Lays out a practical view of what proof looks like — for founders building, and investors underwriting

If you’re building something ambitious, this is the bit that matters: proof is a sequence grounded in evidence.

Important: This article is for information purposes only and does not constitute financial, legal, or tax advice. It is not an offer or solicitation to buy or sell any investment. Investing in early-stage companies is high risk and illiquid, and investors may lose all of their capital.

Quick takeaways

- Deep tech is grounded in scientific discovery or meaningful engineering innovation — not a brand label. [1][5]

- Deep tech companies often face technical risk first, then market risk — which changes what “traction” means. [1][2]

- The fastest way to lose credibility is to confuse a demo with proof.

- Proof looks like a stack: feasibility → reproducibility → reliability → economics → deployability → adoption.

- Deep tech is now a mainstream venture category — but it can still be underwritten poorly by those lacking experience and mistake excitement for evidence. [2]

- The best founders narrate progress through de-risking milestones, not hype cycles. [1]

What is deep tech?

A definition you can actually use

A useful definition is one that helps you decide what to do next.

Here’s a working definition that holds up in the real world:

Deep tech refers to technologies whose core advantage comes from scientific or engineering breakthroughs, and whose path to market requires meaningful R&D, patient capital and de-risking; creating products that solve complex global problems. [1][5]

Deep tech isn’t a “sector”. It’s a type of advantage.

Common deep tech domains

Deep tech is often used to describe fields like:

- artificial intelligence (AI)

- advanced materials

- biotech and synthetic biology

- robotics

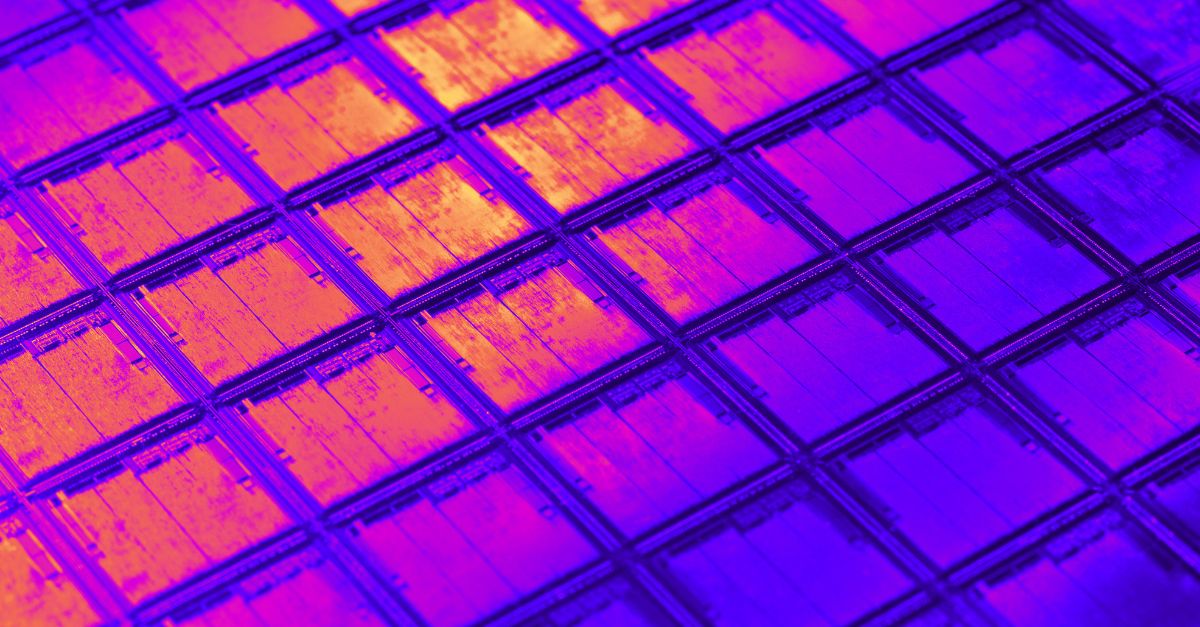

- photonics and semiconductors

- cyber and secure infrastructure

- compute and future of compute

- fusion and advanced energy

- quantum technologies

The domain list is less important than the shape of proof required to win.

What deep tech isn’t (and why this matters)

It isn’t “any startup with smart people or PhDs”

If your core differentiation is execution, distribution, or user experience — that can still be a brilliant company. It’s just not necessarily deep tech.

Deep tech implies the advantage is tightly coupled to:

- a scientific insight

- an engineering breakthrough

- a hard-to-reproduce capability (often IP, know-how, process, or data + physics) [1]

It isn’t “AI, but with more maths”

A lot of “AI startups” are building application-layer workflows. Those can scale fast — but their proof is usually commercial (retention, CAC/LTV), not scientific.

Deep tech AI tends to sit where the constraint is physical or infrastructural: compute efficiency, hardware, data centre bottlenecks, reliability, safety, security, or resilience — the things that break when systems meet reality. [1][2]

It isn’t a synonym for “hard tech”

“Hard tech” often implies tangible products and manufacturing complexity. Deep tech can include hard tech — but it also includes breakthroughs that may ship as software, services, or platforms. [1]

Why the distinction matters: if you call everything deep tech, you destroy the signal. Founders lose credibility, investors misprice risk, and the market becomes noisier than it needs to be. [1]

Deep tech vs “regular tech”: the risk profile is the point

Technical risk comes first

In many software businesses, you can prove product-market fit before the product is “finished”.

In deep tech, the first battle is usually:

- reproducibility

- reliability

- safety and compliance

- manufacturability

- cost curves

That changes how you plan your team, your funding, your narrative, and your definition of progress. [1][2]

Timelines are longer — and that’s not a moral failing

Long cycles don’t mean you’re failing. They mean you’re building something where reality has veto power.

What matters is whether the timeline is intentional:

- Are you running the right experiments to collapse uncertainty?

- Are you proving the constraints that buyers and operators actually care about?

- Are you building a path to scale, not just a path to another demo?

Deep tech often takes longer between funding stages, and the capital plan should reflect that. [2]

The proof stack: what “progress” looks like in deep tech

Most founders don’t fail because the technology is impossible. They fail because they can’t show the right proof at the right time. A useful mental model is to treat progress as a de-risking cycle rather than a single leap from lab to market. [1]

Here’s a practical proof stack you can use as a roadmap. Think of it as a sequence of questions you must answer, in order.

Proof layer 1: Feasibility (does it work?)

You need credible evidence the mechanism holds:

- a prototype demonstrating the core effect

- measurement that is repeatable and defensible

- ideally, independent replication (even partial)

Founder trap: confusing “works once” with “works”.

Proof layer 2: Reproducibility (can you repeat it?)

Reproducibility is where deep tech stops being a lab curiosity and becomes a company:

- results hold across conditions and operators

- measurement methodology is explicit

- iterations are tracked (your version history matters)

If you can’t reproduce it, you can’t scale it. And if you can’t scale it, you can’t sell it.

Proof layer 3: Reliability and safety (can you trust it?)

For anything touching critical systems, reliability is the product.

Proof here often looks like:

- defined failure modes and mitigations

- validation and verification plans

- safety cases and compliance pathways

- evidence of stable performance under stress, not just best-case conditions

Proof layer 4: Economics (can it work at a price?)

Deep tech dies in spreadsheets.

You need a view on:

- unit economics at scale (even if range-based)

- manufacturing constraints and yields

- supply chain dependencies

- capital vs operational expenditure trade-offs for customers (capex vs opex)

A founder who can talk about cost curves credibly is often miles ahead of one who can talk about “market size” fluently.

Proof layer 5: Deployability (can it survive the real world?)

This is where “pilot” becomes a dangerous word.

Deployability means:

- integration into existing systems

- maintenance model and operational ownership

- training burden and failure recovery

- compliance in situ

- what happens on a Tuesday at 3am, not in a demo

Proof layer 6: Adoption (will anyone roll it out?)

Adoption proof is rarely “a signed pilot”. It’s evidence the buyer can:

- justify spend internally

- manage risk and compliance

- operationalise the change

If the operational narrative doesn’t work, the technology doesn’t ship — no matter how elegant it is. [2][4]

What proof looks like for founders (practical milestones)

Use TRLs* if they help — but don’t hide behind them

Readiness frameworks can be useful shorthand. But they’re not proof by themselves.

A credible founder narrative sounds like:

- “Here’s what failed last quarter. Here’s what changed. Here’s what now holds.”

- “Here are the constraints we can’t beat yet — and the experiment that answers them.”

*Technology Readiness Level – a system used to assess the maturity and readiness of a technology.

Build a de-risking map investors can read in 60 seconds

Investors don’t need certainty. They need clarity. Treat deep tech progress as explicit de-risking: what uncertainty are you collapsing next, and what evidence will count as a real answer? [1]

A de-risking map includes:

- the top technical uncertainties

- the next experiment to collapse uncertainty

- cost/time to run it

- what a “pass” and “fail” implies

This makes fundraising faster, and it forces discipline internally.

Decide what you’re proving next (and what can wait)

Deep tech teams burn time by proving the wrong thing.

A simple rule:

Prove what unlocks the next decision, not what makes the deck look better.

What proof looks like for investors

Underwrite the stack, not the story

Deep tech can look “inevitable” in a pitch deck. Reality doesn’t care.

Strong underwriting asks:

- which proof layer are we truly at?

- what evidence supports it?

- what’s the next gating uncertainty?

- who buys first, and why will they tolerate the risk?

- where does capital intensity spike (and when)?

Deep tech investing is increasingly treated as a distinct, established opportunity set — but it still requires different judgement than pure software. [2][4]

Look for “inevitable if true”

A strong deep tech company often has this property:

If the technical claim is true, the value is obvious, and the market risk is constrained by necessity (not preference).

That’s different from many consumer or workflow products, where preference changes can erase value overnight and hype cycles create bubbles that inevitably pop.

Price the “late-stage wall”

Deep tech often hits funding walls later:

- scale-up capital needs

- manufacturing ramp complexity

- regulated rollouts

- long procurement cycles

If you don’t plan for the wall, you’ll hit it at the worst possible time. [2][4]

Deep tech commercialisation: why most “pilots” don’t convert

If you only remember one thing: a pilot is not traction. It’s an audition.

The three reasons pilots stall

- No operational owner

- No integration plan

- No risk narrative

Design pilots backwards from rollout

A pilot that converts is built around:

- success metrics that operations and procurement recognise

- a pre-agreed decision process for rollout

- an integration and maintenance plan from day one

- a credible compliance/risk story (not bolted on later)

Deep tech commercialisation often depends as much on adoption pathways as it does on the underlying technology. [4]

Deep tech proof in practice: three mini case patterns

Pattern 1: The physics breakthrough

- Feasibility proven early

- Reproducibility takes longer than expected

- Scaling hinges on manufacturing and reliability, not the core effect

Pattern 2: The regulated pathway

- The product works

- The business is gated by approval, evidence, workflow redesign

- Proof is operational and clinical, not just technical

Pattern 3: The infrastructure constraint

- The market is created by bottlenecks (power, cooling, network, security)

- Proof is total system improvement, not component performance

- Buyers care about reliability and integration more than novelty

How to talk about deep tech without sounding like everyone else

Use constraint language

In deep tech, credibility isn’t created by how big the vision sounds. It’s created by how precisely you can describe the limits your technology works within.

Constraint language is simply this: you describe performance with the real-world conditions attached.

Because in deep tech, the only version of “works” that matters is:

- works repeatedly

- under the conditions the buyer cares about

- at a cost the buyer can defend

- inside the system the buyer already has

That’s what makes the difference between “interesting” and “deployable”.

FAQs

What is deep tech in simple terms?

Deep tech is technology built on scientific discovery or meaningful engineering innovation where progress depends on R&D and validation — not just distribution. [1][5]

What’s the difference between deep tech and hard tech?

Hard tech usually implies physical products and manufacturing complexity. Deep tech is broader and can include software, platforms, and systems. [1]

How do investors evaluate deep tech startups before revenue?

By underwriting feasibility, reproducibility, reliability, economics, deployability, and a credible commercial pathway — essentially, the proof stack and the de-risking plan. [1][2]

Why do deep tech pilots fail to convert?

Because technical success isn’t enough: pilots stall without an owner, an integration plan, and a procurement-grade risk narrative. [4]

What does traction mean in deep tech?

Early traction often means proof progression (repeatability, reliability, economics, deployability) rather than pure revenue. [1][2]

Conclusion

Deep tech is not a badge. It’s a commitment to building technology where the hard part is real, and the proof is grounded in evidence.

If you’re a founder, your job is to move through the proof stack by collapsing uncertainty in the order that makes rollout possible. If you’re an investor, your edge is knowing which proofs matter now, which can wait, and which are being quietly avoided. Deep tech timelines are longer, funding needs are different, and credibility is earned by de-risking, not by theatre. [1][2]

At Amadeus, our lens is problem-first: we back trailblazers solving hard problems in large markets, and we care deeply about what it takes to prove those solutions in the real world.

References

- MIT REAP — What is “Deep Tech” and what are Deep Tech Ventures?

- BCG — An Investor’s Guide to Deep Tech

- Royal Academy of Engineering — State of UK Deep Tech 2025

- McKinsey — European deep tech: what investors need to know

- HSBC Innovation Banking — Demystifying deep tech